Building a Circular City: What Are We Missing?

A look at some common assumptions, biases and challenges in envisioning circular cities

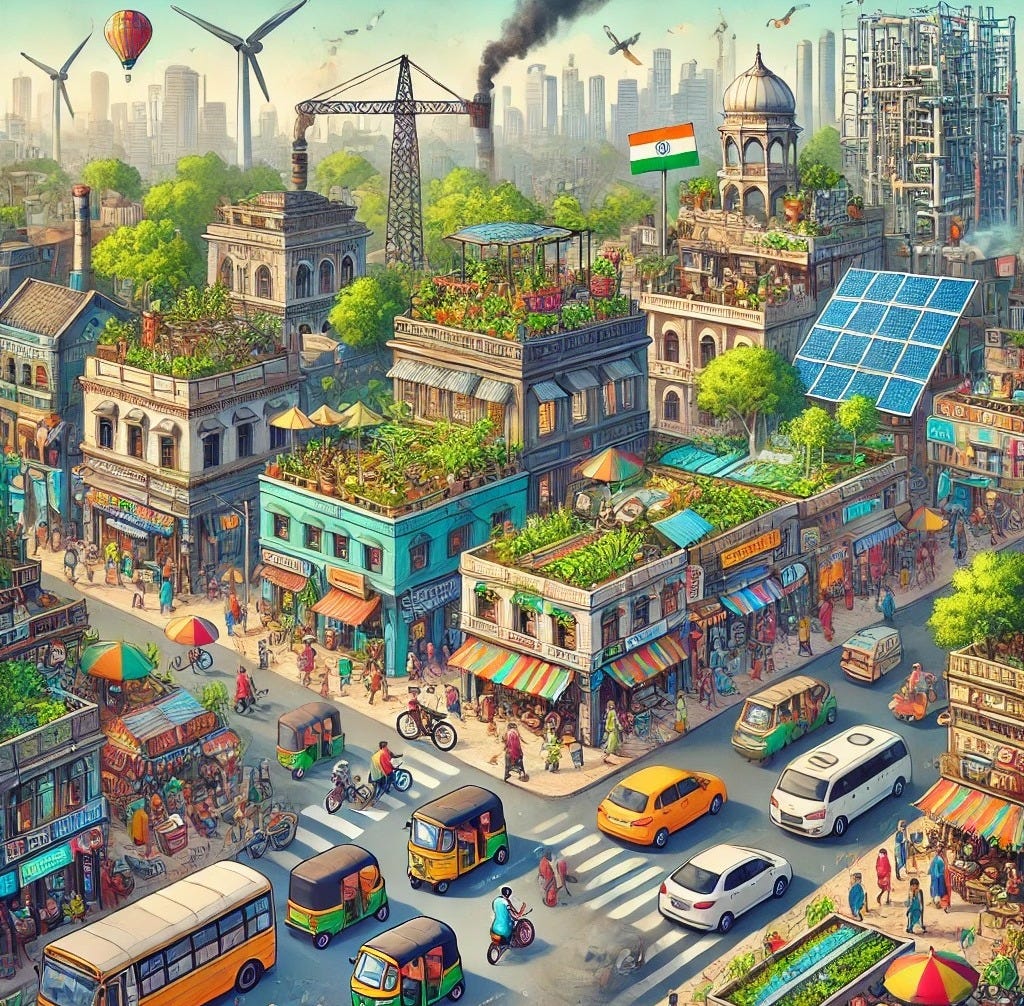

Last fortnight, we read about one vision of how a circular city would look which can be read below.

But getting there isn’t perfect. The challenges are widely known and discussed. So today we want to get the conversation going by shedding light on under-discussed areas.

Today, I want to highlight some assumptions, some fairly questionable assumptions, some biases in the vision I shared and the challenges that lay ahead. Each of these is addressed by looking from the eyes of an energy transition engineer, an urban planner, a policy maker and an economist respectively.

Assumptions

One assumption that is valid is the possibility of designing and reaping the benefits of smart city designs. Integration of renewable energy, building energy-positive and energy-neutral buildings is achievable.1 Management of material, waste management does allow for a fairly circular model. Decentralizing technologies, though having their pros and cons, do make building a circular city a possibility.

The next assumptions sustainable land use and efficient transport systems. The reduction in road space for private vehicles in favour of public transport, cycling lanes, and pedestrian pathways align with the principles of sustainable urban mobility. Mixed-use development allows for walkable cities, reducing the necessity to travel. Adapting older buildings and repurposing them allows for smarter usage of existing resources. Such development is done keeping community at the core of planning through constant feedback.

The policy decisions required to make the city in the story real are aligned with that of India’s goals towards becoming a net zero economy. Decentralization brings autonomy to local bodies which is imperative to ensure a circular economy. Another assumption made is the active and aggressive policies to reduce private travel and boost local businesses and assistance to transition into them2.

Another assumption is that the transition to a circular economy can drive job creation in green sectors. Circular economy principles, such as recycling, renewable energy production, and sustainable urban agriculture, can open up new markets and generate employment opportunities. The reduction in commuting, thanks to hybrid work models, would also lead to economic benefits, lowering transportation costs and reducing the strain on urban infrastructure. Moreover, the increased efficiency in resource use through circular practices would contribute to long-term economic sustainability.

And the stakes are incredibly high when we plan something in the long term. That implies, we need to verify the assumptions that we lay down as the foundations for our visions. Some of them, may not be as valid as we believe them to be.

Questionable Assumptions

Based on the story in the previous edition, there are certain points to note. It assumes a near universal adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) which is a far-reaching dream due to challenges with battery technologies keeping recyclability in mind. Building with recycled materials is a great option, but scaling up the technology comes with a fair bit of scepticism. While the story focused a lot on long termism and future-proofing, it reduced the severity and importance of tackling short term issues. Another assumption , glaringly wrong at the moment, is that all industries can turn circular, like industries that require high temperatures, shipping and aviation, cement etc.

From the viewpoint of an urban planner, the assumption that the city can rapidly adopt circular economy practices without facing planning and regulatory challenges is overly optimistic. The idea of greenspaces and rooftop garden/public spaces/ agriculture is appealing, it overlooks the challenges of ensuring equitable access to these spaces. The large socio-economic disparities of today cannot directly be solved through technology and infrastructure alone. Hybrid work as a norm is not applicable to a wide variety of jobs, and it is also not applicable across all socio-economic classes.

Developing policies without setbacks is impossible, furthermore, with such a complex problem, some well-intentioned policies (and well-implemented ones) will fail due to the lack of knowledge of the behaviours impacting various subsystems or unexpected factors. The second, is of course, is the power available to implement such policies. Another assumption that doesn’t hold true is the universal acceptance of policies without significant resistance from stakeholders. Above all, the assumption that the general public is educated and has the power to hold the local policymakers accountable is highly questionable.

Financial mechanisms to shift to circular methods are untested and need to become more lucrative for businesses (especially the biggest businesses - you know who) to bring in trust in such methods. There is a need for high risk appetite for untested applications for technologies, in a not-so-mature economy that has focused on stability of masses since freedom. Decentralisation and self-sufficiency practically ignore the need for trade both locally and internationally and impacts of external markets.

Biases

The story exhibits a bias toward technological solutions, assuming that they can address most urban challenges without considering their broader socio-technical implications. While engineers recognize the potential of technology to improve resource efficiency and sustainability, the bias lies in underestimating the complexity of integrating these technologies into existing systems. For example, while solar panels and smart grids are effective, their implementation depends on factors like infrastructure compatibility, cost, and social acceptance, which are often glossed over in the narrative.

Technology-centric urbanism shows bias towards the impact of technology to drive urban change. The story neglects the lack of access. There is a massive rural-urban disconnect which implied the city is a self-driving machine while ignoring its dependence on rural or non-urban areas (and trade) for its sustenance. Another bias is revealed in believing that there would be a uniform impact of such interventions in cities across all locations, while in reality, wealthier neighbourhoods would be the largest beneficiaries. The story neglects other issues like affordable housing, public health and sanitation and completely ignores the informal sector that runs the economy of India.3

Decentralization is great. Panchayats and municipalities are attempts at it, but they still are under a tight leash by states and the centre. Hence, it would be a huge bias to state as a fact that it will work. The expectation that political parties have common agendas without pursuing their secondary individual ideologies with minimal lobbying is a tough pill to swallow. Policymakers are not well-educated on all facets of circular economics and may not have the skills to collaborate with each other. And the biggest bias is that of idealization of capacity, expertise and resources (financial, human and material) to implement the frameworks and policies.

The story is biased toward assuming that green and circular economy products will automatically generate sufficient consumer demand. Economists recognize that market demand for sustainable goods depends on price competitiveness, consumer preferences, and perceived value. The bias here lies in overestimating consumers' (of all financial backgrounds) willingness to pay for sustainable alternatives, especially if they are more expensive than conventional products. Additionally, the assumption that all economic sectors can quickly adapt to circular economy principles overlooks the complexities of market dynamics and supply chains.

4. Challenges

One of the major challenges from an engineering perspective is the retrofitting of existing infrastructure to accommodate new technologies like smart grids, renewable energy systems, and water management solutions. In densely populated cities with aging infrastructure, these upgrades are both technically challenging and expensive. Engineers must address issues such as integration with existing systems, ensuring reliability, and minimizing disruptions during implementation. The challenge is compounded by the need for skilled labour, technological innovation, and long-term maintenance.

For urban planners, the challenge lies in balancing sustainability with rapid urbanization. Indian cities are growing at an unprecedented rate, and planners must manage this growth while ensuring that infrastructure, housing, and services align with circular economy principles. This involves overcoming regulatory and political hurdles, coordinating between various government agencies, and securing the necessary funding for large-scale urban projects for some of the most densely populated cities in the world! Informal settlements and slums lack basic necessities, and upgrading them would be a mammoth task. Cities in India are already overburdened. Other challenges would include coordination of governance and policymakers, socioeconomic diversity, cultural and religious resistance and financial and institutional constraints.

For a country plagued with issues to ensure the population at least reaches the second rung of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, thinking about sustainable growth is a herculean task. Policymakers need to be educated and educate the public4. The issue of addressing the informal sector, the underprivileged and underdeveloped areas cannot be overlooked, while also focus on resilience and disaster preparedness. Land rights and resource distribution is another challenge that policymakers must address. And finally, the question of financing, expensive technologies and projects with long-term returns on investment (many of which are intangible) while ensuring they are re-elected every five years plagues everyone.

The primary challenge is financing the transition to a circular economy. The investments required to upgrade infrastructure, support new businesses, and incentivize sustainable practices are substantial. Securing this financing through public-private partnerships, green bonds, or international climate funds is essential but challenging. Additionally, managing the economic displacement caused by the transition, such as job losses in traditional industries and the need for retraining workers, requires careful planning and resource allocation.

In the end…

The takeaways from this article are the following:

Have respectable conversations and discussions on making your cities livable and healthy by going circular.

To allow you to accept multiple visions of circular cities by recognising people's (and most importantly, your) valid and invalid assumptions and biases.

After recognising these, it should give you a better understanding of the subject and recognise the limits of your (and others and my) knowledge and expertise.

Finally, the realisation that everyone’s ideal circular city is flawed and we need to collaborate to fight the wrongs in our individual stories to build a collectively correct story.

So, how would you envision a city?

Footnotes

Renewable energy, as a sustainable alternative, is critical in reducing emissions, with advances in technologies like solar and geothermal helping to transform energy usage in buildings. Here is the paper.

Here is an analysis of circular economic policies. This gives perspectives to understand challenges and biases as well.

The article - Circular Cities: A Key to a Truly Sustainable Urban India, gives a good overview into the specifics of what goes into planning and some major factors that need to be tackled.

The book Poor economics by Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo is quite insightful when we think about the mindset a significant amount of people in India who need to be on board and who also need to benefit from our ideas of circular cities.